I had an opportunity to provide community education through Fusion Burlington in a live zoom-based webinar titled “Parents, Educators, and Children Striving for Balance this Fall.” I was joined by our host, Matt Shea from fusion Burlington and privileged with an engaging and enthusiastic audience.  The talk focused a lot on parents‘ decision-making for best supporting a child’s emotional wellness moving towards the fall session of school in the midst of remote and hybrid models of learning. I discussed the importance of circadian rhythm’s, human relationships, challenging growth opportunities for growing capacities and skills, and educational endeavors.  Throughout the talk, I highlighted the fact that a child’s mood behavior, energy, sleep, what and when they eat, how much they exercise, and things they’re exposed to in the environment (e.g., sunlight, temperature) are all interconnected. As we know, change, unpredictability, and performance demands will create stress for all involved as we moved towards the fall. Attention to circadian rhythms, including all of the things stated above can help address the tension.  An engaged parent asked how to motivate a child to comply with parents surrounding the aforementioned activities, and this led to a conversation surrounding the importance of balancing warmth and control in parenting, the topic of scaffolding, and just how important certain parent skills such as praise, paraphrase, and validation are in the parent-child relationship. I promoted high expectations for a child’s conduct and compliance, since we are supporting children towards health today, and also towards skills to prepare them for adulthood, as well.  On the topic of balance we discussed the balance between attending to stress versus inviting challenges. I noted developmental challenges often tend to include growing emotional capacity and mastering daily living skills. We also discussed the delicate balance between leaning on the school for support, and also drawing upon private and public resources outside of the school.  I ended with recommendations for teachers. I recommended they engage their own self-care, lean on their own supports, communicate promptly with each other, support each other, monitor the situations as they progress through the year, and create connection and predictability for children. I drew from a recent article by Eric M Anderman & Kui Xie, which suggested that teachers should go out of their way to build relationships with students, place academic material into context by stating the relevance of the material, and develop new rituals and routines throughout the day. On a personal note, I’ll add this this experience was extremely pleasant and enjoyable for me. I think my passion for the material combined with the enthusiasm in the participants allowed for positive energy, which made the experience such fun. I’m grateful to fusion Academy and to all the participants who attended so that we could think together about how to best care for ourselves and foster health and learning for children this fall.

0 Comments

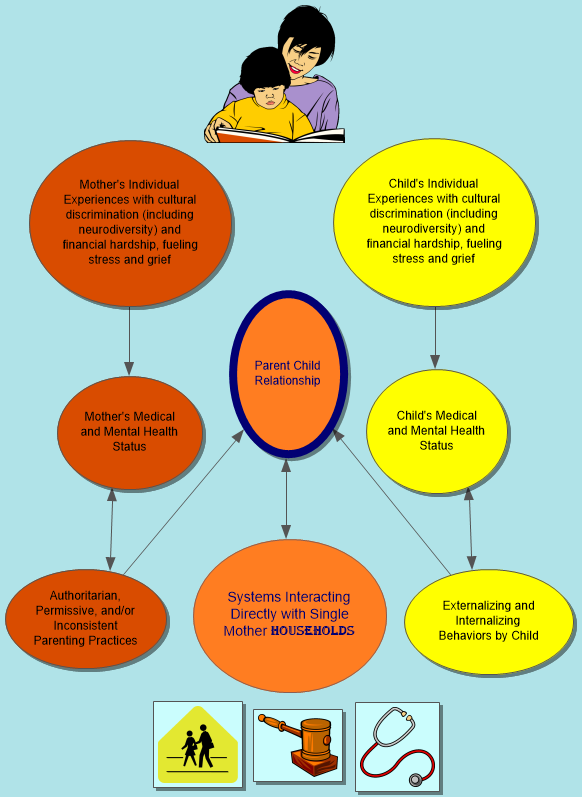

5/24/2020 0 Comments Parenting Concerns: Preventing and Addressing Clinical Anxiety During a Pandemic4/20/2020 0 Comments REFLECTIONS DURING COVID-19: HAVE WE BEEN CRIPPLING CHILDREN'S LIFELINES By Marginalizing Women ?Many households throughout the world are coping with the new normal of staying at home to flatten the curve and to safely ride out the medical emergency brought on by Coronavirus-19 (COVID-19). The sudden change in living, working, and parenting has brought stress, reticence, and grief into homes. Physical distance and face masks are the new norm. Some people are working remotely, sometimes at a faster pace, seemingly for longer hours. Meanwhile, many people are out of work or have businesses that are in trouble financially, and they are hoping for financial relief. The range of childhood experiences unfolding during COVID-19 remind us of the variety of life experiences that can happen across and within social and demographic groups. During the pandemic, some children are at home engaging in activities such as karate and music lessons via live streaming. Some are cooking or baking. Some in semi-rural and rural areas may be enjoying a retreat to a simpler time, reading, landscaping, and helping out in the garden. Meanwhile, many children and teens feel trapped, with nowhere to go, and little stimulation from the outside world. This is perhaps due to being in the small space of an apartments, or perhaps for other life, familial, or individual reasons. So, a subsection of the population includes children across socioeconomic groups who are isolated and stressed during COVID-19. While managing stress and uncertainty, some parents have circumstances and resources that allow them to adjust to the new conditions quite smoothly, whereas many do not. Working from home, many parents feel pressure to morph into educators as their children complete the school day at home. This is especially true for parents of children with specific learning needs. Schoolwork is the tip of the iceberg. Some parents are worried about potential exposures to the virus if they take their children to the pediatrician for medical needs unrelated to COVID-19. Some separated parents feel strain surrounding shared custody and related movement of children between homes, particularly given the societal expectation to “shelter in place.” Some parents have left their children for extended periods of time because of their own work, because of travel restrictions, or because of a family members’ illness. Parents risking exposure to the virus while at work are concerned that they could be endangering their own lives or the lives of their children. Some parents are spending hours online trying to stock up on groceries to ensure that there is food in the house, some are wearing masks and venturing into grocery stores, while many parents are stopping off at schools and food banks, grateful for the assistance so they may feed their children. Some are looking at their finances and trying to budget for taxes. Some don't have any money, and are waiting for some financial relief from the government. Parents are questioning, “What are realistic educational, medical, parenting, and financial expectations for me and for my children during this pandemic?” COVID-19 has caused devastating loss of life, pain, and stress upon so many. It has accentuated the best and the worst of our culture. It shines a light on our resilience and adaptability, and it also re-reveals our inequitable society. Deaths due to this illness have been distributed unevenly across demographics, and this is because of previously established and preventable health disparities (Graham, 2020). COVID-19, with the suffering it has brought on, has given us a moment to look at what we have collectively created as a society. “Mobilizing to confront the pandemic and, eventually, to reconstruct the shattered economy, requires not only medical and economic expertise but also moral and political renewal.” - Michael Sandel, April 19, 2020, Opinion, New York Times I am writing now in the hopes of mobilizing local schools, hospitals, legal institutions, and colleagues. I am inviting your interest in affecting social injustices in order to influence the physical and psychological health of historically disenfranchised groups of children and their parents. As a practicing Psychologist, I am aware that these social, psychological, and medical factors are all interconnected. Even as I write about hardship and suffering, I think it is important to note that, as we face COVID-19 together, the profession of mental health knows that not all people will walk away with pathological anxiety or trauma. History and my clinical training informs me that resilience will arise, and this will be observed across demographics, including subgroups being unfairly burdened (e.g., grocery clerks, hospital workers). Expectedly, people across demographics will draw upon internal resources (e.g., hope, desire, good-will) and systemic resources (e.g., family, friends) as they process their experiences. Nonetheless, we owe it to ourselves to reconsider our treatment of historically marginalized groups (i.e., How are we each contributing to the marginalization? What are we actually doing to combat it?) and to do so on a personal level, as well as in our leadership behavior in organizations and communities. Child Responses to COVID-19 in a Private Practice I specialize with children, and thus have observed a range of responses to COVID-19 by a variety of children who are patients. My patients tend to be 3-17 year olds, represent neurodiversity (i.e., ADHD, ASD, Dyslexia, NVLD), and have mild to severe challenges with mood and anxiety. Their struggle with mood and anxiety is something that they managed before COVID-19. They are a diverse group socially, culturally, and economically. Some patients’ families are in the top 1% of the income bracket, while other patients’ families are living from check to check and receiving some form of public assistance. For the group of children and teens I work with, this past month has been a mixed bag of relief, disappointment, and opportunity. Some are happy that they get a moment to be with family, and relieved that they don’t face the same social pressures that they encountered in school. Some are grateful that their parents are validating and offering structure at this time. Some are feeling reduced stress. They enjoy a break from this fast-paced neurotypical society. Some are finally taking time to focus on sleep, exercise, and protein intake. Almost all of them miss their closest friends. Many of my patients are trying to navigate schoolwork without the full spectrum of special education services in place. During this pandemic, schoolwork has been particularly taxing on young neurodiverse children and their families in instances where there was a lack of productive teamwork between the school and the family before COVID-19, or where educational needs were not being fully met before the pandemic. Some of the more emotionally and behaviorally impaired patients are struggling with circadian rhythms and coping skills, the very issues that were present before the pandemic. A couple were thrust out of needed residential and psychiatric hospital settings due to COVID-19 and now they cannot access the level of care that would be best. Marginalized Children and Families Before and After COVID-19: Illuminating Injustices As has been discussed in the Boston Globe and elsewhere, there are portions of the population that are far more impacted by the crisis due to the inequitable world we live in, due to health disparities, due to systemic prejudice, and because of discrimination. Previously known health disparities which we have co-created over the years are interacting with COVID-19 and disproportionately taking lives. "Even in a global health crisis, Black and brown people can’t practice social distancing from the systemic, institutional, and foundational racism that overshadows and undermines our lives." - Renee Graham, The Boston Globe, April 10, 2020 I have been thinking a lot about disenfranchised kids (e.g., children with learning differences, children who are biracial, children who represent “the racial minority” in their schools, and children in single parent homes). This has been on my mind because this has been a long-standing topic of concern, and also because this is a subgroup of my caseload. It is my experience that children in my caseload who are in single parent homes, black, have learning disabilities, are immigrants, or are in the minority in their school entered the COVID-19 situation without all of their needs met due to systemic injustice. While talented and capable in countless ways, while bringing intellect and creativity to the table, many of these children have been stressed, and their gifts seem squandered. Children who are immigrants deal with student-on-student harassment, harsh discipline in schools, civil rights violations, subtle and not-so-subtle pressure to conform and abandon their culture, and possible language barriers without proper accommodations (Koch, Gin, & Knutson, n.d.; Grossman & Liang, 2008). The below realities also ring true to me as I think about patients in my practice: “Black students and students with disabilities are more likely to receive harsh school discipline than their counterparts” (American Psychological Association, The Pathway from Exclusionary Discipline to the School to Prison Pipeline). Marginalized Women Single mothers are dealing with added stress associated with limited resources, limited family and leisure time, maternal chronic health concerns, increased child needs, some of which are due to discrimination, toxic to their well being (Benner, Wang, Shen, & Boyle, et al. 2018), and now they manage increased risk of exposure to COVID-19. It is within this context that I would like to discuss the plight of single mothers representing cultural diversity (e.g., women of color, immigrants) and those who have escaped intimate partner violence, many of whom are managing economic strain while attempting to best care for their children. Right now, my largest concern is for these parents and their children before, during, and following COVID-19. “The #coronavirus pandemic has exposed the lack of infrastructure, support, resources and care for single parents, most of which are women. Flexible work arrangements must be applied at all levels to support the economic security of every family. #COVID19” - Tweet by UN Women, April 3rd, 2020 Single mothers tend to be marginalized, stigmatized, manage multiple roles, have relatively less job satisfaction, and struggle to access needed resources (Richard & Lee, 2019). These stressors are thought to cause maternal psychopathology and can undermine parents’ ability to parent mindfully, consistently, and with warmth (Daryanai, Hamilton, Abramson, & Alloy, 2016). Stress due to marginalization and discrimination can generally spill over into relationships (Barton, Beach, & Bryant, et al., 2018), and I sometimes observe this in parent-child relationships in single parent homes. In some cases, I have been offering evidence based services for years with these children, which has included everything I know, all of my knowledge, skill, and ability, and it seems as though the single parents households and I are paddling against the current and working hard only to stay in one place. In other words, after offering evidence based treatment with a strong alliance with the parents and children, systems of care in place, and collaboration with the child’s medical and mental health team, I’m still observing health disparities in my own practice. And these disparities cut across culture. They are related to single parent homes. I invite you to entertain the thought that the broader systems we are existing within could be the strong current working against these families and hindering potential treatment gains. I'd like to consider the hypothesis that broader systems are inadvertently undermining parents, and therefore undermining treatment. Thus, the very best treatments we can offer these children aren't enough, given the context. If my hypothesis is true, we must do more than train the parents, we must address the broader systems. What needs to change in the broader systems? For years, I have observed microaggressions inadvertently cast at single mothers, sometimes in ways that are known to the kids. I notice school and community partnerships seem so fragile. The families and I are jointly wondering, are these broader systems based issues the main problem? In other words, are the single mothers the scapegoat for the schools’, hospitals’, and courts’ shortcomings? Dare we ask that question? When it comes to children with disabilities and children of color in single parent homes, I conceptualized the broader systems (e.g., schools, hospitals, courts, police, and other helpers) as the metaphorical “other parent,” having the potential to strengthen or undermine the mother’s authority in the child’s eyes. Having contemplated the issues with the families I work with, I believe undermining the single mother’s authority has the potential to cripple the child’s lifeline and direct the child towards the “school to prison pipeline.” Perhaps mindfulness and productive teamwork practiced by professionals with these mothers could make a world of difference for these children and put a barrier in the pipeline. Moms Who Are Women Of Color Especially for single moms who are women of color and managing financial strain, there is a constant effort to find a way to get what a child needs and a sense of pain and frustration when there aren't enough resources. There wasn’t enough social and community support before COVID-19 for these parents, and now that we face this pandemic, resources are even more slim and risks are higher. One of the parents I partner with is working in the community, thereby putting her life in danger out of financial necessity. Being in a physically unsafe situation can be quite stirring, and she handles the stress with grace. Meanwhile, without adequate special education services in place (both before and during the pandemic), based upon her child’s grades on assignments, she is aware that her child is failing to understand the material in school. Previously unaddressed learning needs are showing up in the quality of the child’s work. With COVID-19, previously unmet learning needs are being accentuated. Over the years, I have observed implicit bias and related micro- and macro-aggressions directed towards this mother and it is heart wrenching to observe. Once, I came across a report to the Department of Children and Families (DCF) regarding this mother from a “professional” in one system. The report was so blatantly racist that even DCF acknowledged the illegal nature of the report and swiftly moved on. This kind of transgression by a “professional” in a school system reflects the ways in which systems have the capacity to inflict harm on single parent families, and children who are often aware of such transgressions. In my view, this particular instance was highly damaging to the child and the parent-child unit. Mothers Who Are Immigrants Mothers who are immigrants are sometimes lawyers, physicians, educators and other professionals in their homeland. While they cannot practice here in the US, these individuals bring great intellect and capability to their communities. They may raise their children in a way that brings the best of their own culture integrated with American culture, offering a stronger foundation for their children. In my view, cultural knowledge is like the mortar in the foundation of the child’s self esteem, deepening a sense of pride in their family and themselves. In the US, immigrant families I have worked with tell me that there is sometimes a sense of being “othered” and they sense they are perceived as having lesser value or of being less entitled to resources. So, competition is expressed towards them within the community. In the context of a highly homogenous, mostly white New England community, one mother, a professional who is an immigrant, described being seen as “exotic” and strange by some community members. One mother who is an immigrant described being ignored by community members in public settings. Another mother explained that people in homogeneously white communities seem to like the idea of diversity in theory, but then struggle to embrace diversity when implementation of culturally sensitive practices are recommended. She noted, “In theory, people might want to be ‘welcoming,’ yet struggle to truly integrate us into their lives.” The psychological literature on the topic of immigration validates these women’s voices (Koch, Gin, & Knutson, n.d.; Meyers, Aumer, & Schoniwitz, et al., 2020). And, I observe the effect of such mistreatment. I see these single mothers who are immigrants begin to question their own social, psychological, and cognitive capacities. Sometimes I see them internalizing the oppression and blaming themselves for the challenges they face in their social environment, including their challenges in parenting their children. I see the way that microaggressions in their environment sometimes chip away at their maternal-esteem and undermine their ability to confidently raise their children. Worse, I observe their children internalize the messages from the mainstream that their mother has less value. Managing COVID-19 which gets in the way of communication, already strained, has the potential to further isolate and alienate these mothers and their children. Mothers and Children Exposed to Domestic Violence During the pandemic and before the pandemic, I’ve been concerned about women and children who have histories of domestic violence in the home. Some of these women have been exposed to shared traumas with their children and have shown incredible resilience to get their child to a new situation which is physically safe. They bring their children with them to my office and ask that I help them to address the issues that the child is managing. Because I’m a solo practitioner, I’m not in a position to pick up children or families in the throes of active violence. Therefore the mothers I’m consulting to have escaped domestic violence and are picking up the pieces with their children. Children exposed to domestic violence are often traumatized “may develop distorted and maladaptive views of relationships and may assume age-inappropriate roles and responsibilities within the context of their relationships with parents” (Intimate Partner Abuse and Relationship Violence Working Group, 2001). Cooperativeness, helping attitudes, and charitability can be hindered by such early childhood stress (Jirsaraie, Ranby & Albeck, 2019). They can sometimes tend towards externalizing or aggression due to childhood exposure to violence (Intimate Partner Abuse and Relationship Violence Working Group, 2001). These children can sometimes be difficult to parent, and more likely during times of stress and when questions of physical safety are present. For these children, powerlessness felt around COVID-19 combined with limited resources and strained relationships is highly jarring. The mothers are using every bit of their energy to intentionally develop strong parenting practices, and they are attempting to work productively with mental health providers, schools, hospitals, and legal systems. They have their minds set that they want their children well, and they want their children to flourish. I have observed ER staff, due to unconscious bias, inadvertently minimize children’s very predictable psychological issues. The reality is that, in light of early exposure to violence, we can predict that these children might not come out of their past unscathed and that externalizing tendencies may present after the exposure to violence (Intimate Partner Abuse and Relationship Violence Working Group, 2001). I see these mothers with histories of intimate partner violence judged as maintaining the child’s very predictable issues. The above-mentioned data gets ignored as mothers in these circumstances often get blamed for the child’s very predictable challenges. There is a huge stigma surrounding intimate partner violence. I observe that parenting a child following such a situation can be extremely challenging, taxing, and isolating. Doing this during a pandemic seems excruciating. In my view, these mothers are some of the least understood and most undermined in their parenting practices. Recommendations Recommendations for Schools, Hospitals, and Legal Institutions School, hospitals, and legal professionals, I hope to reach you. You interact with these children and parents. I’d like to bolster your curiosity about the context in which these mothers and their children are situated, now during COVID-19, and also as we move forward. These mothers and children need your assistance. I am reaching out today because I believe that you are positioned to make things better. Mostly my recommendations relate to partnering and teaming with single parent households. This is because, in my view, the wellness of children with single parents depends upon our ability to partner. This includes our willingness and ability to communicate in a timely manner, to provide support, to embody patience, and to mindfully monitor the situations in which children with single parents exist. Such teamwork could make a big difference for them and especially for their children. I recommend you do the following:

Recommendations for Researchers I hypothesize that implicit bias and related inadvertent microaggressions towards the parent in front of the child, and also recommendations made by schools, hospitals, clinics, or the legal system have the potential to affect parent-child relationships. I recommend that we study the effect of the communications between systems and parent-child dyads on the quality of parent-child relationships. We already know about the effects of community hardship on maternal mental health; the effects of socioeconomic hardship, violence, and discrimination on children’s mental health; the effect of maternal stress and mental health on parent child relationships; the effects of parenting skills on parent child relations; and of child psychopathology on parent-child relations (Choi & Kangas, 2020; Daryanai, Hamilton, Abramson, & Alloy, 2016; Goldstein, Harvey, & Friedman-Weieneth, 2007; Gurwitch, Messer, & Masse, et al., 2015; Herr, Jones, & Cohn, et al., 2015; Kagan, Frank, & Kendall, 2017) But what about the effect of systems’ communications with the parent-child dyad? Please consider this as a topic of study. Recommendations for Communities While we are waiting for the research to catch up, I’d like to put out a request that right now we take a moment to reflect. Let us be mindful regarding our biases and judgments about culture, immigration, women, domestic violence, and socioeconomic status because such biases may inadvertently fuel microaggressions in front of mother-child dyads who represent these populations. It is my perspective, based on anecdotal data in my everyday practice that microaggressions cast at the mother in front of the child have the potential to chip away at the foundation of the parent-child relationship. This can be a particularly toxic recipe for these vulnerable dyads of parents and their children. Community members, please note, undiagnosed learning disabilities and unmet learning needs can wreak havoc on a young child's emotional health. There is a reason the school to prison pipeline includes children with learning disabilities. You can help create a solution. For children who seem stressed by schoolwork, whose family has financial hardship, and who comes from a historically marginalized group or single parent household, community grants could be made available to offer these children thorough neuropsychological evaluations. Such assessments could be life altering for many children. Such assessments could ensure adults in the children's lives are aware of each child's academic, emotional, and psychological needs. Needed assessments may make it easier for adults to work together to meet children’s needs, and lead to less misunderstandings regarding these children and the source of challenges. Recommendations for Psychologists We as Psychologists need to partner more effectively, educate more honestly, & we need to set our sights on lending a hand to families struggling with limited resources. We need to help correct the many misunderstandings regarding the source of those families’ troubles. We as helpers, all of us, providers in private practice, schools, hospitals - have got to stop waving a finger at single parent households and start looking at the ways in which we are contributing to the problems that these parents face with their children. We must draw upon science to inform our thinking. And, let’s not disregard what we see with our own eyes. Please note: The above blog is not meant to be a commentary on my local school district, which I’ve been partnering closely with, but more a reflection of regional and national trends. References

American Psychological Association. Single parenting and today's family. https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/single-parent American Psychological Association. The Pathway from Exclusionary Discipline to the School to Prison Pipeline. https://www.apa.org/advocacy/health-disparities/discipline-facts.pdf American Psychological Association Intimate Partner Abuse and Relationship Violence Working Group (August, 2001). Presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association in San Francisco. https://www.apa.org/about/division/activities/partner-abuse.pdf American Psychological Association,Task Force on Socioeconomic Status. (2007). Report of the APA Task Force on Socioeconomic Status. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/task-force-2006.pdf American Psychological Association (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the school? And evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist Vol. 63, No. 9, 852–862. https://www.apa.org/pubs/info/reports/zero-tolerance.pdf Barnes, J. C., & Motz, R. T. (2018). Reducing racial inequalities in adulthood arrest by reducing inequalities in school discipline: Evidence from the school-to-prison pipeline. Developmental Psychology, 54(12), 2328–2340. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dev0000613 Barton, A. W., Beach, S. R. H., & Bryant, C. M., et al. (2018). Stress Spillover, African Americans’ Couple and Health Outcomes, and the Stress-Buffering Effect of Family-Centered Prevention. Journal of Family Psychology, Volume 32 (2), 186-196. Benner, A. D., Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Boyle, A. E., Polk, R., & Cheng, Y. P.(2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolesce. American Psychologist, 73 (7), 855-883. Choi, K. J., & Kangas, M. (2020). Impact of maternal betrayal trauma on parent and child well-being: Attachment style and emotion regulation as moderators. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000492 Cui, L., Criss, M. M., Ratliff, E., Wu, Z., Houltberg, B. J., Silk, J. S., & Morris, A. S. (2020). Longitudinal links between maternal and peer emotion socialization and adolescent girls’ socioemotional adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 595–607. Cardenas, J., Taylor, L., & Adelman, H. S. (1993). Transition support for immigrant students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 21, 203-210. Cardichon, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Protecting students’ civil rights: The federal role in school discipline. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Daryanai, I, Hamilton, J.L., Abramson, L.Y., & Alloy, L.B. (2016) Single Mother Parenting and Adolescent Psychopathology, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(7): 1411–1423. Department of Justice (n.d.). Educational opportunities case summaries. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/edu/documents/classlist.php Girvan, E. J., Gion, C., McIntosh, K., & Smolkowski, K. (2017). The relative contribution of subjective office referrals to racial disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(3), 392–404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/spq0000178 Goldstein, L.H., Harvey, E.A. & Friedman-Weieneth, J.L. (2007). Examining Subtypes of Behavior Problems Among 3-Year-Old Children, Part III: Investigating Differences in Parenting Practices and Parenting Stress. J Abnorm Child Psychol 35, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9047-6 Gonzalez, L. M., Borders, L. D., Hines, E.M., Villalba, J. A., & Henderson, A. (2013). Parental involvement in children’s education: Considerations for school counselors working with Latino immigrant families. Professional School Counseling, 16, 185-193. Graham, R. (2020) Being a person of color isn’t a risk factor for coronavirus. Living in a racist country is. Boston Globe: Opinion. Updated April 10, 2020. Grissom & Redding (2016). Discretion and Disproportionality: Explaining the Underrepresentation of High-Achieving Students of Color in Gifted Programs. AERA Open. Vol .2 (1) pp 1-25. Gurwitch, R. H., Messer, E. P., Masse, J. J., Olafson, E., Boat, B. W., & Putnam, F. W. (2015). Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement (CARE): An evidence-informed program for children with a history of trauma and other behavioral challenges. Child Abuse & Neglect. Online access. Herr, N. R., Jones, A.C., Cohn, D. M., & Weber, D.M. (2015 ). The Impact of Validation and Invalidation on Aggression in Individuals With Emotion Regulation Difficulties. Personality Disorders, Theory, Research, and Treatment, Vol 6 (310-314) Jirsaraie, R. J., Ranby, K.W., & Albeck, D.S. (2019). Early life stress moderates the relationship between age and prosocial behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, Volume 94. Juang, L.P. & Alvarez, A.N. (2011) Family, School, and Neighborhood: Links to Chinese American Adolescent Perceptions of Racial/Ethnic Discrimination. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 2 (1) 1-12. Kagan, E. R., Frank, H. E., & Kendall, P. C. (2017). Accommodation in youth with OCD and anxiety. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24(1), 78-98. Kirwan Institute (2019). Understanding implicit bias. Retrieved from http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/understanding-implicit-bias/ Koch, J.M., Gin, L. & Knutson. Creating safe and welcoming environments for immigrant children and families. https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/safe-schools/immigrant-children.pdf Koch, J. (2007). How schools can best support Somali students and their families. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 9, 1-15. Meyers, C., Aumer, K., Schoniwitz, A., et al (2020) Experiences With Microaggressions and Discrimination in Racially Diverse and Homogeneously White Contexts. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, Vol. 26, No. 2, 250–259 Monahan, K. C., VanDerhei, S., Bechtold, J., & Cauffman, E. (2014). From the school yard to the squad car: School discipline, truancy, and arrest. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(7), 1110–1122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0103-1 Morrison, S., & Bryan, J. (2014). Addressing the challenges and needs of English-speaking Caribbean immigrant students: Guidelines for school counselors. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 36, 440-449. Mowen, T., & Brent, J. (2016). School discipline as a turning point: The cumulative effect of suspension on arrest. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 53(5), 628–653. Okonofua, J. A., Paunesku, D., & Walton, G. M. (2016). A brief intervention to encourage empathic discipline halves suspension rates among adolescents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Olneck, M. R. (2004). Immigrants and education in the United States. In J. A. Banks & C. M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (pp. 381-403). New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. Olsen, L. (1997). Made in America: Immigrant students in our public schools. New York: The New Press. Phelps, T. M. (2014, May 8). School bias against immigrant children called ‘troubling.’ The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com. Ramey, D. M. (2016). The influence of early school punishment and therapy/medication on social control experiences during young adulthood [Abstract]. Criminology, 54(1), 113-141. Richard. J. Y. & Lee, H. (2019). A qualitative study of racial minority single mothers' work experience. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66 (2), 143-157. Sandel, M. (2020) Are We All in This Together? The pandemic has helpfully scrambled how we value everyone’s economic and social roles. Opinion, New York Times. April 13th. Teaching Tolerance (2013). Best practices: Engaging limited English proficient students and families. Retrieved from http://www.tolerance.org. Tamer, M. (2014). The education of immigrant children: As the demography of the U.S. continues to shift, how can schools best serve their changing population? Retrieved from https://www.gse.harvard.edu. The Center for Health and Health Care in Schools. (2013). School based mental health –building cultural connections and competence. Retrieved from http://www.healthinschools.org. U.S. Department of Education. (2014). Education services for immigrant children and those recently arrived to the United States. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov. United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (2018). Civil rights data collection: school climate and safety. Data Snapshot: School Discipline.” http://ocrdata.ed.gov/Downloads/CRDC-School-Discipline-Snapshot.pdf. United States Government Accountability Office (2018). Discipline Disparities for Black students, boys, and students with Disabilities. Report to Congressional Requesters. https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/690828.pdf Welch, K., & Payne, A. A. (2010). Racial threat and punitive school discipline. Social Problems, 57(1), 25–48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/ sp.2010.57.1.25 Williams, F. C., & Butler, S. K. (2003). Concerns of newly arrived immigrant students: Implications for school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 7, 9-14. Zong, J., & Batalova, J. (2015). Frequently requested statistics on immigrants and immigration in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org. 3/31/2020 2 Comments GETTING BACK TO THE BASICS OF PARENTING DURING A PANDEMIC: PARAPHRASE, PRAISE, & VALIDATE I am sharing a picture of myself from not so long ago when I'd unwind by getting my hair done at the salon (Thanks again Alketa Hawes and the rest of the staff at Mane Escape! Miss you!). This photo was taken before COVID-19 took hold of Massachusetts and just before people began physically distancing here in my community. This was taken before a huge portion of parents were spending long days alone with their children at home. And, even then, I was expressing concern about our society’s seemingly limited understanding of child development and of the lack of developmentally-friendly communication skills being used with children and teens. And now, more than ever, I believe that adults need to get back to basics and re-learn three fundamental skills when interacting with children and teens. These skills are: 1. To paraphrase overtures. 2. To praise / acknowledge efforts. 3. To validate emotions. I’d like to discuss the importance of each of these developmentally friendly communication skills, and share some of my experiences learning and teaching these skills. I often share these reflections with colleagues and clients, and it seems that this is a time when the broader population may benefit from hearing this perspective. Paraphrase Paraphrasing is one of those simple critical skills a psychotherapist learns to practice early in their training and education. It falls under active listening. It’s also one of the most central skills a developmental expert learns in the context of play therapy and parent-child interaction therapy. Additionally paraphrasing is found in most couples counseling manuals. Before my husband and I got married, I enrolled us in a couples counseling program at UCLA (Go Bruins!). Based on years of being contently married (20 yrs.), it seemed that the couples counseling program was effective. Paraphrasing was the first skill that we learned. And, anyone in organizational psychology knows that paraphrasing is in the active listening activities that one would be taught in an organizational context. Adults working in high stakes teams such as hospital teams and military teams learn to paraphrase in a timely manner. For communication purposes, paraphrasing is an important ingredient in confirming that the listener heard what the speaker had to say. Having paraphrased communications by children and teens for thousands of hours, and having trained parents to engage the skills for countless hours, it seems evident to me that children want to be heard and that adults struggle mightily to slow down and listen to what they have to say. Paraphrasing is such a simple skill. Yet, I’m stunned at the degree to which parents and educators struggle to simply paraphrase what a child or teen says. Especially when a child or teen has something painful or unpopular to say, it seems that adults cannot tolerate just hearing it and reflecting it back accurately. Sometimes adults argue it is redundant to paraphrase. And sometimes parents and teachers worry that paraphrasing signals an endorsement of what the child or teen says. Whatever the reasons, when I first ask a parent to paraphrase in a role-play, typically what comes out is far from paraphrasing. Parents and educators, even counselors for that matter, rather than paraphrase, tend to pose questions, seek insight, and infer. What I typically get from them is projection. Sometimes I wonder when we stopped being with children in a mindful and reflective way and began turning parents and educators into pseudo psychoanalysts whose job it is to understand the source of the child’s words. When did it stop being enough to reflectively be with a child? Everywhere I turn there’s an armchair therapist waiting to get to the inner workings of the child’s expressions. Most of my work with parents and with educators is to get them to refrain from all of the analysis and coaching that they are attempting. Sometimes I think parents and educators seek insight because Freudian psychoanalysis made its way into mainstream culture and cannot seem to find its way out (I imagine even the psychoanalysts among us would not want such processes playing out in peoples living rooms). Sometimes I think parents and teachers feel intellectually bored with young minds and are simply entertaining themselves cognitively with all of their musings. Sometimes I think the culture has just become incredibly neurotic (as I feel trying to understand why parents and educators struggle to paraphrase). But it doesn’t matter, really, why parents and teachers do the things they do. In my view, they just need to stop all of the interpretations of the child and simply learn to listen to the child and reflect. Just hear the child. Just hear what the child or teen says, and concretely reflect it back. Don’t add to the demands. Don’t psychoanalyze. Simply reflect back what they’re saying. What happens when parents do this? What happens when educators do this? Just by engaging this skill, I see kids’ moods lift. I see kids warm up to adults. Unfortunately, those who research parent-child interactions have failed to study the effect of paraphrasing specifically on the child’s mood. Ironically, they’ve looked more at its effect on conduct and behavior, and there, we see a positive effect. And we do also think paraphrasing increases interpersonal bonds. I expect if and when the relationship between adult paraphrasing and child mood is studied, we will discover that there is a positive shift in the moods of kids whose parents and teachers learn to paraphrase. Praise Praise is feedback. Praise let’s a person know that what they are doing is pleasing to others. Without it, a person may be lost in a sea of disconnection and isolation, and wonder if her contribution is of value to others. Praise offers live guidance. It is much easier to find our way when we try something and get immediate feedback or guidance. From a task as simple as building an IKEA table to as complex as teaching a class of students, we may all benefit from experience and practice with immediate feedback. Praise is a form of immediate feedback. Imagine this, in the classroom, a child shares about his dog and peers smile. A child may answer a question in class correctly and a teacher may enthusiastically reply, “yes!” These subtle acknowledgements emotionally connect, and subtly direct, children in the classroom. Praise takes this sort of feedback just a bit further. It is more specific. Rather than, “yes” the teacher might say, “I love the detail you provided just now in your answer.” Praise as positive feedback is used across settings. Praise tends to be used in the context of psychotherapeutic relationships. Praise is used in coaching relationships, as well. Praise is used in corporate teams.Praise is used in marketing endeavors. Being ignored in a group is a great way to understand what it is like to have a dearth of praise in one’s life. Being neglected and unappreciated is a lonely place. Due to a combination of oppression and gender socialization, young females differentially use praise and ignoring to uplift some peers and, conversely, to harm other peers. In this tactic called “relational aggression,” they will praise someone who they want to embolden, while overtly ignoring someone who they want to harm. Whereas being ignored shuts people down, praise, a form of feedback or positive reinforcement, pulls us towards relationship. It lifts us up. People are often motivated to stay in places and remain in connection with others in spaces where they tend to be praised, acknowledged, and uplifted. And, getting praise has the power to enhance self efficacy, a sense of being capable of affecting things in a social setting. When I encourage parents to praise their children, I get a number of different responses. Many parents only need a reminder to praise and some practice with praising more often. However, some parents feel so infuriated with their child that the only kind of praise they can imagine giving their child would be disingenuous praise. They ask, “so you want me to kiss up to my child?” I’ve met some parents and teachers who seem so hardened and burned out that the idea of engaging soft skills like praise seems like “pussy footing.” In such situations, the idea of acknowledging the child and giving positive feedback seems initially like too much to give. It’s like they’re too stuck in battle with their child, and they can’t imagine letting down their own guard. Conversely, some parents fear that the use of praise is too controlling or too manipulative. They worry that they are belittling their child by engaging praise. They believe their child is higher minded than someone who would need praise and acknowledgment to get through particular tasks. Sometimes these parents report that they, themselves would feel belittled by praise. And, they prefer longer conversations and negotiations and problem-solving endeavors. It is my perspective that they see their child as a small adult rather than a young, developing person. It’s not uncommon for parents to praise their child on one hand and then, in the next breath, to comment about the child’s past failures or mistakes. For such parents, it may be difficult to be in the moment and express some acknowledgment and gratitude for that particular moment in time with the child or teen. What I observe is that parents are surprised with the results when they take a leap of faith and learn to engage specific praise. I believe we see these results because kids need more direction and connection than we realize. They aren’t fully forms adults, they are kids, after all, and they require our guidance, support, and nurturance. Validate To emotionally validate a child or teen is to communicate that their emotions are human and natural in the context of their experience. When a child or teen is emotionally validated, they are more likely to experience acceptance of their own emotions. Acceptance of emotions allows one to move through emotions and function more adaptively. Conversely, invalidation, or parental rejection of a child or teen’s emotions tends to result in 1. less internal acceptance of emotions by the child or teen; 2. aggression towards parents who invalidate; or 3. both. So there is risk for invalidation to cause a child or teen to become more brittle in the context of internal experiences associated with emotions, and also to become less adaptive and related within their home environment. Often people have the perspective that validation is agreement or sharing similar experiences or simply sympathizing with a child or teen. Often when people hear that it’s important to validate their child, they think it’s important to simply say back to their child, “I can understand how that would be hard for you.“ But in psychology, the skills of validation is different than that. Done well, emotional validation leaves a child feeling as though their emotions are natural and human, and also that the emotions make sense in the context in which the child or teen is situated. I’ve noticed that people who struggle with mood dysregulation often endorse histories where they were not emotionally validated enough in their childhood. Additionally, research shows that people with even mild degrees of mood dysregulation tend to respond with aggression when faced with invalidation. Whereas validation is associated with mental wellness, invalidation is associated with mood dysregulation and aggression. Validation is one of the primary skills taught in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT®) , which is an intervention specifically geared towards people with interpersonal challenges in the context of severe mood dysregulation. If a child with mood dysregulation is placed in a setting such as McLean Hospital, a Harvard affiliated psychiatric hospital, the child and the family will be taught the skill of emotional validation. It is thought to be the most potent and therapeutic skill that one can teach. It’s tough to validate another person when their experience is so far from our own experience. I also notice that it is difficult for parents to validate kids when the parent feels guilty or overwhelmed by the child or teen’s emotions. It seems as though those parents feeling overwhelmed and struggle themselves to work through their own emotions, and therefore struggle to accept their child’s emotions. Given the blocks and barriers to emotional validation by parents, it can be helpful to take a more formulaic approach to the skill of validation. Adherence to the components in the skill of validation may ensure an increased likelihood that the child or teen may experience the benefit of validation. Sometimes teens are particularly sensitive to emotions or “affect phobic” and can’t seem to tolerate validation, even validation done well. Perhaps this is because it accentuates their emotion, and they happen to be fearful of their own emotions. In such situations, I encourage parents to practice validation of each other’s emotions in the home. So, in this way, parents are modeling validation, labeling emotions, and priming skills that eventually the teen should learn. References Agguire, B. Having A Life Worth Living - Dr Aguirre's Insights on Borderline Personality Disorder://youtu.be/JChwgwU9zIs Agguire, B. (2018) McLean Hospital Fall Leadership Conference. Adolescent Mental Health: The Role of Validation https://www.nyscoss.org/img/uploads/2018_Fall_Leader/9.23-4-5-Aguirre-VALIDATION.pdf Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Vicarious reinforcement and imitative learning. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(6), 601-607. Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63(3), 575-582. Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11-34). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association. Baumrind, D. (1991). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In P. A. Cowan & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Advances in family research series. Family transitions (pp. 111-163). Hillsdale, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Ehrenreich-May, J., Kennedy, S. M., Sherman, J. A., Bilek, E. L., Buzzella, B. A., Bennett, S. M., & Barlow, D. H. (2018). Programs that work. Unified protocols for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in children and adolescents: Therapist guide. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. Gurwitch, R. H., Messer, E. P., Masse, J. J., Olafson, E., Boat, B. W., & Putnam, F. W. (2015). Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement (CARE): An evidence-informed program for children with a history of trauma and other behavioral challenges. Child Abuse & Neglect. Online access. Herr, N. R., Jones, A.C., Cohn, D. M., & Weber, D.M. (2015 ). The Impact of Validation and Invalidation on Aggression in Individuals With Emotion Regulation Difficulties. Personality Disorders, Theory, Research, and Treatment, Vol 6 (310-314) Kagan, E. R., Frank, H. E., & Kendall, P. C. (2017). Accommodation in youth with OCD and anxiety. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24(1), 78-98. Linehan, M.M. (2015) DBT® Skills Training Manual: Second Edition. The Guilford Press, New York, NY. Masse, J.J., McNeil, C.B., Wagner, S.M., & Chorney, D.B. (2008). Parent-child interaction therapy and high functioning autism: A conceptual overview. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 4, 714-735. MGH Clay Center. (2014). Sasha’s Story [Video File]. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/90135351 Sunrise Residential Treatment Center. (2014, Dec 15). Relational DBT Validation [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HANLHwZ47Hc Teach Teamwork: An Evidence-Based Self-Guided Program on How to Work Effectively in Teams. This was a joint endeavor by University of Central Florida, The Coalition for Psychology in Schools and Education, and The Center for Psychology in Schools and Education. Link: www.apa.org/education/k12/teach-teamwork.aspx |

AuthorKarin Maria Hodges, Psy.D. CategoriesAll Diversity Hospitals Learning Disabilities Legal System Parenting Schools School To Prison Pipeline Archives |

Dr. Karin Maria Hodges

c/o Raising Moxie

45 Walden Street

Unit 2G

Concord, MA 01742

Office: (978) 610-6919

Cell Phone: (603) 313-5907

c/o Raising Moxie

45 Walden Street

Unit 2G

Concord, MA 01742

Office: (978) 610-6919

Cell Phone: (603) 313-5907

Surf’sUP Method is a service mark of Karin Maria Hodges, Psy.D. PLLC.

No claim is made to the exclusive right to use the word “METHOD” apart from the mark, as shown.

Raising Moxie is a service mark of Raising Moxie, LLC

No claim is made to the exclusive right to use the word “METHOD” apart from the mark, as shown.

Raising Moxie is a service mark of Raising Moxie, LLC